Where in the social hierarchy people found themselves in the Middle Ages determined not only what foodstuffs they could afford, but also how their food was prepared. The most basic form of cooking food was on an open fire. Eggs in their shells, for instance, could easily be cooked this way. When their contents were broken directly on the embers, such eggs were called “lost eggs” (oeufs perdus in French, or verlorene eier in German). Before eating these eggs it was advisable to clean off the ash.1 Most members of the lower classes, when they had a roof over their heads, lived in one-room dwellings with a fireplace in the center that served as a source of heat, a source of light, and a cooking facility. Stones were used to contain the fire. If the walls of the building were not of wood but of stone, the fireplace was often moved away from the center and against one of the walls.2

A basic piece of equipment for any medieval cook was the cast iron cauldron that either had legs already molded to its body or was placed on a ring, usually with three legs, that was set in the coals. Alternatively, the cauldron could be hung from an adjustable hook attached to a beam or to a chimney crane, an iron arm swinging horizontally. This had the advantage that the heat could be better regulated to avoid burning the food. When earthenware pots were used by the housewife, she would either place them in the hot ashes beside the fire or put them on a hot stone in the coals. Since boiling and stewing were the most economical ways of preparing food because no valuable juices were lost, and because only the most basic of cooking facilities were needed, the typical dish of the lower classes was the potage or stew. In fact, from the French word for cauldron, chaudière, comes the modern English word “chowder.”3

Bread was a foodstuff much more difficult, if not impossible, for a housewife of modest means to bake in her own home. If she had the necessary grain, she needed to have it ground to flour first, and lords of the manor usually insisted that she pay a licensed miller to do that rather than do it in small batches in her own mortar or quern, a primitive hand mill. And even if she had the bread dough kneaded and the loaf ready to go in the oven, she had to find an oven. In medieval villages and towns ovens were few and far between, and their construction and operation closely regulated. Only the baker and some of the wealthier households would be granted permission to have such a cooking facility that used up a lot of valuable firewood. As substitutes for a full-sized baker’s oven, households would sometimes use covered pots that they buried in the coals, or small portable ovens. The latter were especially popular in southern France.4

The richer the household in the Middle Ages, the better equipped its kitchen was, the more refined its cuisine, and the greater the likelihood that the food was not prepared by a lone housewife, but by one or more professional cooks with an army of helpers. Monasteries, manor houses, castles, and the houses of the wealthy bourgeoisie were the places where cooks exercised their craft, if they did not run their own business. Like many other professions at the time, cooks were organized in guilds. To become a master cook in Paris, for instance, one had to first work as an apprentice for two years, and then as a journeyman for another master.5 Having attained the title of master, a cook had several options: he could open his own cookshop, work for another master, or seek employment in a wealthy household. The relatively low pay cooks received compared to members of other professions suggests that their status in society was not particularly high. There were exceptions, of course, such as the famous Taillevent, chief cook of the king of France, who was handsomely rewarded for his services and was even given a coat of arms. Judging from the literary sources, however, it would appear that on the whole cooks suffered from an image problem in the Middle Ages, a time in which the spirit was held in much higher esteem than the body, at least by the educated elite. Hence the work of a scribe copying a religious text was regarded as vastly superior to that of a cook who catered to the needs of the flesh.6 Aside from their perceived lack of education, cooks and their staff were often looked down upon because their job was a messy and smelly one that made them reek of kitchen odors. Furthermore, they were accused of drinking on the job, of being hot-tempered and crotchety, and of possessing a rough sense of humor. In their defense it must be pointed out that their job was not always easy, besieged as they were by boarders, nibblers, and tasters, who were not only of the human kind, but included dogs, cats, foxes, rats, mice, and flies, to name a few. Little wonder, then, that cooks were known to use their trademark ladle, with which they were usually depicted, not just to taste the food but also to discipline and chase away the various interlopers.7

But how did cooks themselves view their profession? The little evidence we have suggests that at least when it came to aristocratic cooks, they regarded their work as much more than just a craft. Master Chi-quart, chief cook to the duke of Savoy, for instance, saw himself as an artist and a scientist.8 Entrusted with the health and well-being of

their employers and families, not to speak of the many high-ranking guests they had to feed in the course of the year, cooks worked closely with court physicians, and even if cooks could not read Latin, they must have had some basic knowledge of the medieval theory of nutrition. Food was regarded as the primary means to keep the four humors in the human body in balance, and to rein in any excessive humor with a diet that was appropriate for the particular humoral imbalance.9 In addition to this scientific knowledge, and mastery of the various cooking methods, a good cook was also expected to possess artistic talent. With appearance playing such an important role in the medieval dining experience, it was up to the cook to devise dishes in ever more intricate shapes and colors, and to entertain the dinner guests with illusion food that would do any modern magician proud.

But if the invention of a memorable dish was the crowning of a cook’s career, immortalized perhaps in the chronicle describing the banquet at which it was served, most of the work the cook and his kitchen staff had to perform day in and day out was unglamorous, tedious, and tiring. Being in charge of supplies from firewood to foodstuffs and kitchenware, cooks usually had to report their expenses daily to their superiors, the kitchen clerks or the steward.10 The household of the duke of Burgundy employed three cooks, of whom one was the chief cook or master. Taking orders from the cooks were 25 specialists and their helpers, among them a roaster, a pottager, and a larderer, who was in charge of the larder where the food was stored. Given the real and perceived danger of poison in medieval upper-class households, the office of the cook was one of trust. In his absence the cook was to be replaced by the roaster, with the pottager being next in line.11 Other specialists at court who did not perform their tasks directly in the kitchen but whose work was nevertheless essential for the preparation of a meal, were the saucers and their helpers, who supplied the standard sauces and made sure that enough salt, vinegar, and verjuice, the sour juice of unripe fruit, was in store, and the fruiters, whose responsibilities extended to candles and tapers as well. Working either from within or outside of noble households were the bakers, pastry cooks, waferers and confectioners, butchers, and poulterers.12 The general rule in wealthy households was, however, to process foodstuffs as much as possible in house, since buying prepared dishes from outside castle walls carried the danger of serving food made from inferior, tainted, or outright poisonous ingredients.

In every medieval kitchen there were also a number of menial jobs that had to be performed. They ranged from hauling firewood and tending the fire to drawing water, scrubbing, and guarding the foodstuffs from theft. At the court of the duke of Burgundy fuellers, fire tenders, potters, and doorkeepers carried out these tasks. But by far the biggest contingent of workers in a big medieval kitchen were the scullions. They were the unpaid apprentices who turned the spits, cleaned the fish, scoured the pots and pans, and usually also slept in the kitchen. Some scullions managed to climb in the hierarchy of the kitchen and end up as cooks or master cooks. The already mentioned Taillevent, chief cook of King Charles V of France, too, began as a kitchen boy in the early fourteenth century.13

The primary workplace where cooks and their staff prepared most of the food was the kitchen. In the early Middle Ages the hearth was still centrally located, even in the wealthier households, with the kitchen and dining hall forming one big room. Gradually the kitchen became a separate room, or in some cases a separate building connected with the main building through a walkway that was usually covered to protect the servitors and their precious cargo from the elements.14 There were several reasons why those who could afford it tried to separate cooking from dining, first and foremost to minimize the danger of fire, but also the noise and the smells emanating from the kitchen area. The big aristocratic and monastic kitchens of the later Middle Ages usually had stone walls and a stone floor, and more than one fireplace built against the walls. The kitchens of the dukes of Burgundy in Dijon, France, for instance, had six stone-hooded hearths built in pairs against three of the four walls. A big window and sinks occupied the fourth wall.15 Windows and louvers in the roof made sure that medieval kitchens were properly ventilated. Derived from the French word l ’ouvert, meaning “the open one,” the louver was a lantern-like structure on the roof that allowed the smoke to escape through openings on the sides. Slatted louvers were closed in bad weather by pulling on a string. More durable and entertaining than these wooden louvers were the ones made of pottery, often in the shape of a head with the smoke escaping through the eyes and mouth.16 Windows and the glow from the fireplaces were the main sources of light in medieval kitchens, complemented at times with candles and torches.

Kitchen waste was either dumped into the river, if the castle or monastery was situated on one, or dumped down a chute into the moat that surrounded the castle walls and was periodically cleaned. In medieval towns householders frequently dumped their garbage directly in the street below, judging from the various laws that tried to curb the practice. City dumps did exist, but they were normally located a distance away, outside city walls.

When one thinks of the logistics of a medieval feast, the first things that usually come to mind are the vast amounts of ingredients necessary to prepare all those fabulous dishes the cookbooks and chronicles tell us about. And yet, any cook, even the best one, would have failed miserably without an adequate supply of firewood to fuel the hearths and ensure that all the food was cooked to perfection. Ordered by the cartloads, dense dry wood was continuously hauled into the kitchen, either through the wide doors or perhaps even some big windows. Toward the end of the Middle Ages coal became more and more popular as a fuel because it produced a more even and longer lasting heat.17 Fire irons were used to spark a fire, which with the help of kindling was gradually turned into the desired blaze. Air from the mouth of a kitchen boy or from bellows also helped in drawing up the flames. Instead of putting out the fire in the evening and starting a new one the next day, householders often chose to leave the embers dormant overnight. Since unattended embers were a fire hazard, a pottery cover with ventilation holes was put over the fire. In towns a special bell was rung in the evening reminding people to put out or cover up their fires. The modern English word “curfew” is derived from the name for this bell, couvre-feu, which in turn was named after the above-mentioned pottery cover.18

To make the most of the fire for cooking took a lot of skill, and medieval cooks were true masters in exploiting the heat for a variety of tasks simultaneously. Big cooking pots were hung above the fire on adjustable hooks that, when attached to swinging chimney cranes, allowed for heat regulation by moving the pot vertically and horizontally to or from the fire. The burning logs were placed in andirons under the pot, and if necessary could be removed to reduce the heat. Sometimes small metal baskets were attached to the upright posts of andirons. Filled with hot coals, they were an extra heat source for a pan or pot placed over them.19 Bigger pots and cauldrons would be placed on tripods or the somewhat lower trivets set over or in the coals.

To make fritters, pots with cooking oil were placed directly in the coals.20 For roasting meat and fish, or for toasting bread, spits and grills were used that were either made of wrought iron or of wood. Varying in length and thickness depending on the size and weight of the food to be roasted—ranging from a small bird to a whole ox— spits were placed either right over the fire or to the side, often resting on the andirons or a similar contraption, and turned by one of the scullions. So as not to be directly exposed to the heat of the fire, these spit turners would frequently do their work behind metal shields.21 To catch the juices and basting liquids dripping from the roasts, a special pan, called lechefrite in French, was put under the spit. This pan was also used for gently heating delicate foods.22 Frying pans came in various depths and sizes, and looked quite similar to the frying pans we still use today. When frying food, cooks either held them directly over the fire or placed them on a tripod above the fire.

In addition to boiling, stewing, roasting, and frying, which could all be done on the hearth, some dishes required baking. Pies, if they were not simply put in a covered pot and embedded in coals, or placed in portable ovens, were baked in bakers’ ovens, and so, of course, was bread. Built either into the masonry of the fireplace where the other cooking took place, or as a separate structure in the bakehouse, the medieval oven was normally heated by lighting a fire within. Once the oven walls were sufficiently hot, the coals and ashes were removed, and the pies, tarts, pastries, and bread were lifted into the oven on a flat hardwood peel.23 If a household employed a cook and a baker or pie maker, the cook would prepare the meat, fish, fruit, or vegetable fillings for the pies and then send them over to the bakery, where they were encased in the pie shells and baked.

Another place where food was handled was the dairy. From the dairymaid’s pails the milk was poured into wide, shallow containers. Due to the lack of refrigeration and pasteurization, most of it was turned into cheese with the help of a cheese press, or into butter in a tall churn.24 Specialized rooms or separate buildings that often supplemented the kitchen were pens for livestock, a brewery, a scullery for washing up, the larder, the cellar, and other storerooms.25 Since the freshness of food was a major concern, larder shelves were constantly monitored for rotting food or the presence of rodents, such as mice and rats. To keep the flies away, meat was put in safes that allowed some airflow.26

To make a medieval kitchen run smoothly, more equipment was needed than the heat source, cauldrons, pots, pans, and the contraptions to place them on or hang them from. Cooks and their staff, all wearing long aprons, did most of the cutting on a solid table that was their main work surface. For meat they used a chopping block. Utensils and containers frequently mentioned or depicted in medieval sources included flesh hooks, long-handled basting spoons, big stirring

spoons, ladles, graters, rasps, sieves, tongs, cleavers, knives, whetstones, mallets, whisks and brooms made of twigs, oven shovels, an assortment of hampers, basins, ewers, flasks, platters, trenchers, saltboxes and saltshakers, and mortars and pestles. Cloth was used both for cooking and, along with scouring sand or ashes and tubs, for cleaning the kitchenware.

One of the most basic tasks in the kitchen was to chop the meat and vegetables with a sharp knife. Often the ingredients were cut up, mixed, and seasoned, and the resulting forcemeat or farce (from Latin farcio meaning “to cram”) was used as a pie filling or stuffing, was formed into meatballs, or re-formed around the animal bones from which the meat had previously been removed.27 In some extreme cases the food had to be treated with a hammer first before it could be further processed. This was the case with the Lenten staple dried cod, known as “stockfish,” which was to be beaten with a hammer, then soaked in warm water prior to cooking.28 In the absence of modern food processors, the mortar and sieve cloth were the most important utensils for preparing the smooth sauces and pastes that were the hallmark of medieval upper-class cuisine. Rooted in the medical-dietetic idea that a foodstuff in granular or powder form “will exert the fullest possible influence when in contact with another substance,” medieval cooks would frequently pound ingredients first in the mortar, then moisten them and filter them through a sieve cloth for the desired fine consistency.29

Every foodstuff in the Middle Ages was assigned a combination of two humoral qualities (warm-dry, warm-moist, cool-dry, or cool-moist). (See Chapter 6.) The humoral composition already predetermined, to some degree, what form of cooking to use. This was especially important for the preparation of meat. A good cook knew that pork was cool and moist, and that these qualities would be counteracted by the warming and drying effect of roasting; or that a hare, like most other wild animals, was warm and dry in nature, hence boiling was the recommended way to prepare it. Frying or baking was used for meats of moderate humors.30 One of the characteristic features of medieval food preparation was multiple cooking. Meat, in particular, was often precooked before it was larded and roasted. This was done to cleanse and firm the flesh, perhaps also to make sure the meat was well done by the time it left the roasting spit.31 The recipe for suckling pig from the oldest German cookbook goes even further. It calls for the animal to be skinned first, the meat to be cooked and returned to the skin, the piglet to be boiled, and later grilled over low heat.32 Fish, too, was subjected to multiple cooking. The same German cookbook contains several recipes for stuffing the prepared meat back into the raw skin and then grilling the fish. In some cases the roasted fish was subjected to an additional cooking process by encasing it in dough and baking it.33

A different kind of multiple cooking is found in a popular entertainment dish served in-between courses at medieval banquets across Europe: the fish prepared in three ways. Keeping the fish in one piece, the tail end is boiled, the middle part roasted, and the front part fried. With each part the appropriate sauce is to be served: green sauce for the boiled part, orange juice for the roasted part, and sauce cameline, a cinnamon-based sauce, for the fried part.34 This suggests that multiple cooking was not just done for reasons of health or taste, but also for fun.

The average housewife or neophyte cook in the Middle Ages, however, was concerned about more fundamental issues than how to prepare a three-way fish. Then as now, temperature and timing were the two most important factors that often meant the difference between success and failure in the preparation of a dish. And both were extremely hard to communicate in a recipe, given that the instruments to measure them were either nonexistent (thermometers), or very crude, if available at all (clocks). Not surprisingly, then, medieval cookbooks are full of helpful hints on how to stop food from boiling over, or burning to the pot, and how to avoid the taste of smoke in a dish.35 With directions as vague as “cook it on a gentle fire,” or “make a tiny fire,” in the culinary literature, a cook had to know from experience—or intuition—what temperature was appropriate for a certain dish, or for a certain step in the preparation of a dish.

The same is true with cooking times. Even if a recipe provides information on the quantities of ingredients, which is rare enough, it almost never provides cooking times in hours or minutes. The best the reader can hope for is a comment referring to a generally known activity like saying a prayer or walking a certain distance. Hence a sauce is to be stirred for as long as it takes to say three Paternosters, nuts are to be boiled for as long as it takes to say a Miserere, some ingredients for mead are to be boiled for as long as it takes to walk around a field, and others for as long as it takes to walk half a mile.36 The weights and measurements used in trade were known to medieval cookbook authors but are seldom mentioned in the recipes. In addition to the occasional gallons, quarts, pints, pounds, ounces, inches and the like, quantities and sizes are often expressed with the help of other foodstuffs, such as eggs, or nuts, or parts of the body, such as the length and width of a finger.37 And then, of course, there are the relative measurements “twice as much as,” “a quarter of the amount of,” or simply “not too much of.”

When it comes to food-related fraud in the Middle Ages, most of it was connected with the weight and quality of foodstuffs. Much of the adulteration that occurred concerned the basic foodstuffs wine, beer, bread, meat, fish, and salt, of which great quantities were traded. Of the high-end products, spices in particular were subject to adulteration. Although they were sold in much smaller quantities than the other foodstuffs, the profit margin was much higher which made them a prime target of fraud. To protect medieval consumers from unfair pricing or food of dubious quality that had the potential of endangering public health, governments passed a variety of laws and also appointed food inspectors. One such law was the Assisa Panis et Cervisae (Assize of Bread and Ale) passed in England in 1266. It regulated the weight and price of bread and ale in relation to corn.38 With weights and measures being far from standardized in medieval Europe, legislation was needed for both wholesalers and retailers of food products.

Wine, for instance, had to be imported in barrels of a certain size. Prior to sale, their contents were measured by the king’s own wine gaugers. Endless confusion was caused when the barrels did not conform to the standard size but a foreign one customary in the wine’s land of origin. On the retail side, too, standard measures regulated the sale of wine and ale in taverns. The adulteration of wine in the Middle Ages took many different forms. Good wine was sometimes mixed with bad, Spanish with French or German wine, or sweet wine from the Mediterranean was counterfeited. There is even evidence of an artificial wine made from pure alcohol and spices with no grape content whatsoever. To ensure that the wine sold in London taverns was in good condition, inspectors known as “searchers” made the rounds and ordered any dubious draughts to be condemned or destroyed. One of the punishments for selling bad wine was to have the taverner drink part of it and pour the rest over his head.

Ale and beer were subject to similar kinds of quality control by officials called Alkonneres in England. Adding water, salt, or resin were some of the ways ale was adulterated, and, of course, consumers would get shortchanged if a measure smaller than the one prescribed by law was used. When in the late Middle Ages Europe gradually switched from ale made with malt and yeast to beer brewed with hops, the once small-scale operations dominated by women known as “alewives” were slowly being replaced by larger breweries run by men.39 Their product tended to be cheaper than the traditional ale. To ensure that only beer of good quality was sold, surveyors inspected the breweries, paying special attention to the purity of the ingredients used.

One group of professionals with an especially bad image in the Middle Ages were bakers. Justified or not, bakers were constantly accused of selling bread of less than the prescribed weight or bread made with inferior dough, or dough contaminated with sand, dirt, cobwebs, ashes, and the like. Since bakers’ ovens were not just used for baking bread but also pies, bakers were at times accused of selling tainted pies, too. According to one such scheme that was uncovered in the City of London, cooks sold kitchen waste to the bakers who in turn filled pies with it and sold them at a handsome profit.40 The standard punishment for a fraudulent baker, as depicted in a medieval manuscript, was to draw him through the street on a sled with the lightweight loaf bound around his neck.41

To prevent the sale of bad meat or fish, a number of measures were taken by authorities that included laws against selling meat by candlelight, reheating cooked meat, inflating meat with air to make it look larger, or stuffing rags into inner organs to add weight. Fresh fish was especially problematic because it had a very short shelf life. Hence it was only supposed to be put on sale for two days, and freshened with water only twice.42

Spices, first and foremost among them pepper, ginger, cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, and saffron, were the ultimate in luxury food in the Middle Ages. According to estimates, western Europe annually imported approximately 1,000 tons of pepper and 1,000 tons of ginger, cloves, nutmeg, and cinnamon combined. The value of these imports was the equivalent of 1.5 million people’s bread supply for a whole year.43 The abundance of spices in medieval cookbooks clearly marks them as an upper-class commodity because an average household in the High Middle Ages could barely afford 20 to 25 grams of pepper, and about the same amount of the other imported spices a year.44 Poor people’s substitutes for imported spices were the garden herbs dill, fennel, chives, leeks, onions, garlic, and parsley. If these were in short supply, the German physician Hieronymus Bock recommended the use of vinegar as a universal seasoning for sauces, fish, crayfish, meat, and cabbage.45 The high price of spices made them attractive for adulteration by spice merchants intent on increasing their profit margin even more. Ground spices especially were frequently mixed with a variety of foreign substances. The officials appointed to examine imported spices were known as “garblers” in England. The term, derived from the verb “to garble” meaning “sifting impurities from,” adequately describes their job, which was primarily to clean spices and dried fruit by sieving them and removing any foreign matter such as leaves or dirt, before grocers were allowed to sell them.46

According to one source, a London apothecary filled the order for ginger, wormwood, and frankincense made by a Gloucestershire merchant by substituting the items with rapeseed and radish, tansy seed, and resin.47 According to Hieronymus Bock, white bread or wheat flour were often mixed in with ground ginger, dried wood with cloves, tanner’s bark or the bark of oak trees with cinnamon powder, and ground nutmeg was frequently nothing more than dry and wrinkled nuts. Saffron was stretched with sandalwood, and sometimes even gold dust was mixed in with the spices to bring them up to the right weight.48 This is an impressive demonstration of the fact that some spices were considered more precious even than gold. Another, more mundane way of increasing the weight of spices was to wet them.49 Peppercorns were adulterated with a whole range of different substances, ranging from unripe juniper berries to vetch (climbing vines of the bean family) to mouse droppings.50

Throughout antiquity and the Middle Ages physicians, too, put together lists of substitute foodstuffs and drugs known as “quid pro quo.” In them ginger is suggested as a substitute for pepper, figs for dates, and hyssop for thyme, for instance. Cheap substitutes that could be grown in one’s garden were savory for pepper, and the root of myrtle flag for ginger. High-priced saffron could be replaced by safflower as a coloring agent. The fact that adulteration of spices was such a widespread problem in the Middle Ages shows what a lucrative business the spice trade was. The quid pro quo lists, on the other hand, are an indication that the poorer segments of medieval society also wanted to emulate the tastes of the upper-class dishes that were laced with expensive imported foodstuffs. This raises the question, what exactly was the taste so sought after by medieval diners?

Spices were used extensively, and in a much wider variety of dishes and drinks than today. They were usually added in powdered form, but sometimes also whole. Ready-made spice mixtures with names such as powdour douce or mild powder, and powdour fort or strong powder, were commercially available. The former often contained sugar and cinnamon, while the latter consisted of more pungent spices such as pepper.51 Judging from the medieval recipes that have come down to us, spices must have played a leading role, and yet we do not really know how dominant their taste was in a given dish. Spices surely lost some of their strength between the time they were harvested in Africa and Asia and the time they finally reached the European consumer, which could be months. Being sold and stored in powder form rather than whole also likely diminished their potency. And, of course, adulteration reduced the quality and strength of spices, if not changing their taste altogether. On top of that, medieval cookbooks hardly ever give amounts for the ingredients to be added.

Aside from spices, acidic liquids were a medieval predilection, one that the lower classes also could afford. Wine, vinegar, and verjuice, or the fermented or unfermented juice of unripe grapes or other unripe fruit, formed the basis for a wide variety of dishes. In the fifteenth century citrus fruits such as lemons, limes, citrons, and bitter oranges, together with pomegranates became part of the repertoire of acidic food substances. Unlike vinegar and verjuice, however, these fruits were exclusive foodstuffs only the upper class could afford. To produce the many sauces that accompanied roast meat, these tart liquids were usually combined with powdered spices and thickened by way of reduction or concentration, bread crumbs, eggs, the liver and breast meat of fowl, ground almonds, or rice flour. Starch was used only rarely as a thickener, and flour, dairy products, or roux, the combination of fat and flour, not at all.52

To counterbalance the tart flavor of the various acidic liquids, sugar, honey, must (unfermented grape juice), dried fruit, and other sweeteners were frequently added giving the dishes the desired sweet-and-sour or bittersweet taste that was the hallmark of medieval European cookery. When it comes to fat, pork fat was the undisputed king in the Middle Ages. Olive oil and nut and seed oils were used in salads—inasmuch as salads were eaten at all in a given region—and these oils were used as substitutes for pork fat on fast days. Butter played a comparatively minor role in the medieval cookbooks. Much more prevalent than the taste of cow’s milk and butter was the taste of almonds. Like the ubiquitous grape juice, almonds were a durable if somewhat pricier foodstuff that was immensely versatile. Not as distinct in flavor as vinegar or verjuice, in fact rather bland, almonds were used in various ways, whole, slivered, or ground, or turned into almond oil, almond milk, or almond butter. The almond’s flavor would either disappear completely, blend in with the other flavors, or be the main flavor, albeit a dainty one, as in the case of marzipan, the famous sweetmeat.53

For those who could not afford the luxury of expensive spices, garden herbs and bulbs were a way to add flavor to their dishes. Leeks, onion, and garlic were popular all over Europe and were often associated with the lower classes. Due in no small part to its odor, garlic especially was considered as peasant food.54 Sometimes as much as the taste, it was the appearance of a dish that mattered. Color and shape were important factors for cooks to consider, especially when they prepared the myriad of dishes that made up a medieval banquet.

Already in Roman times cooks cared about the color of the dishes they prepared. From the third-century cookbook De re coquinaria (The Art of Cooking) attributed to the first-century Roman gourmet Apicius, we learn that a boiled-down wine called defrutum was used to give the gravy of meat dishes a deeper color.55 Adding soda to green vegetables was known even then to brighten the natural color of vegetables. There are also examples of white and green sauces in the cookbook, and saffron already played a role as an additive to wine. And yet, these Roman examples of enhancing and manipulating the color of food were nothing compared to the color craze that swept Europe in the wake of the Crusades to the Holy Land and other contacts by European Christians with the Arabs, notably in Sicily and southern Spain. Gold, red, white, and silver are the colors that abound in the few Arabic cookbooks we have from the Middle Ages. These colors were of enormous significance to Arab alchemists, whose goal was to turn the mercury extracted from cinnabar into gold with the help of sulfur. To create white dishes medieval cooks did not usually color the ingredients but combined those that were by nature white, such as almonds, the white meat of poultry, sugar, rice, and ginger.56

Dramatic effects could be achieved by preparing a dish in batches of different colors and arranging them on a platter with one half white and the other yellow, for instance, or creating the pattern of a checkerboard. Golden yellow, the result of using saffron and/or egg yolk, was the absolute favorite in Arab and European kitchens of the time. Saffron was added ground if an even coloring of the dish was desired, or sprinkled on top of a dish to cover the surface with golden dots or lines.57 A cheaper way of gilding or “endoring” food was to cover it with egg yolk before the final cooking. Meatballs were covered this way in Arabic recipes that eventually made their way into European cookbooks of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Green was a color that had long appealed to Europeans, as the Roman attempts at enhancing its appearance in vegetable dishes has shown. When yellow and green were mixed, it resulted in a bright green that was called gawdy grene in English, and vert gay in French.58 For darker greens, chard, spinach, parsley, mint, basil, and other herbs were used.59 To color a dish, either the pounded leaves or the juice extracted from them was added. Much effort went into creating the various shades of red, from light pink to deep purple, with which cooks delighted the discerning diner. Sandalwood was frequently used and yielded an old-rose color, and draco, or dragon’s blood, was a plant-based dye that resulted in bright reds. The root of the plant alkanet, or dyer’s bugloss, also appears as a food dye in the medieval sources, as do rose petals, blood, and red grape juice. Tournesoc or tournesol, an orchil lichen, gave medieval cooks the option of dying alkali-based dishes blue, which was the plant’s natural color, or red when combined with acids.60 Other ways of creating blues were adding columbine blossoms or blackberry pulp. For the many shades of brown cooks utilized sandalwood, which gave them a pinkish brown, cinnamon for a camel’s hair color, blood for dark brown, or toasted bread or gingerbread, which, depending on the degree of toasting, would produce any shade from light brown to black. Cooked chicken liver, dark raisins, and prunes were other ingredients that could be used to color a dish black. An especially dramatic effect was achieved by covering a dish or part of a dish, such as boar’s head, with gold or silver leaf that was ingested along with the meat and was regarded as having medicinal qualities.

Some types of dishes lent themselves especially well to coloring. Processed foods ranging from liquids to creams and pastes were habitually colored. Roast meat was usually accompanied by sauces that came in all the colors of the rainbow. Some of them were actually known by their color, such as green sauce, white sauce, or the famous camel- or cinnamon-colored sauce known as sauce cameline. Saffron gave many rice and almond dishes a radiant golden hue, and also added sparkle to jellies. A medieval cook could show his mastery of the craft by creating multicolored jellies in the pattern of a checkerboard, for instance, or a round center in one color and an outer ring in a different color.

But color was not the only means to enhance food in the Middle Ages. Another way was to give the processed food a distinctive shape through the use of molds. They seem to have been especially popular in Germany, as, in fact, they still are today. A pan known as a “Turk’s head pan,” presumably named after the shape of a turban it gives to the cake baked in it, continues to be used for making Gugelhupf, a favorite coffee cake.61 But the Turk’s head pan was not a medieval invention. As early as A.D. 200 the Romans used similar molds made of bronze. In the opinion of one scholar, the swirls symbolized to the Romans not a turban, but the rotating sun. Prior to the Romans, the Egyptians were known to prepare sacrificial food in a pan of this type.62

In addition to bronze, clay was used in antiquity for the production of molds. Stone was another durable material for such cooking vessels, but most of them were probably made of wood. Due to the rapid decay of wood, examples of wooden molds from earlier centuries are rare, however. Molds are already mentioned in the oldest German cookbook, as the following recipe illustrates:

Diz ist ein guot spise von eime lahs [This Is a Good Salmon Dish]

Take a salmon, scale it, split and cut the two halves in pieces. Chop parsley, sage, take ground ginger, pepper, anise, and salt to taste. Make a coarse dough according to the size of the pieces, sprinkle the pieces with the spices, and cover them completely with the dough. If you can fit them into a mould, then do so. In this way you can prepare pike, trout, bream, and bake each one in its own dough. If it is a meat-day, however, you can prepare chickens, partridges, pigeons, and pheasants, provided that you have the moulds, and fry them in lard or cook them in their moulds. Take chicken breast or other good meat. This will improve your art of cooking even more, and don’t oversalt.63

When these molds were used for baking in an oven, they were covered on the inside with butter and on the outside with clay. Molds also played an important role in the preparation of gingerbread and confections. To create fully formed shapes, two corresponding molds were used, held in place by aligned holes through which sticks were pushed. At the end of the Middle Ages, molds made of wax are mentioned in the preparation of sugar figurines. Jellies and confections were poured into molds in the shape of boxes. Molds consisting of dough were filled with jelly, according to the fifteenth-century German cook Meister Hannsen.64

Pie shells, too, were cooked in special containers or molds that were first sprinkled with flour, and then boiled in a water bath before being filled with the farce. Some molds had the shape of stamps whose relief was pressed into the marzipan or dough preparation; alternatively, the mixture could also be pressed onto the stamp and then baked. This was a favorite technique of gingerbread makers.

The popularity of waffles and wafers in the Middle Ages, especially at the conclusion of a multicourse meal, meant that waffle irons were part of the standard kitchenware in upper- and middle-class households.

They usually consisted of two flat planes with interlocking handles. Decorations found on the planes could include images or inscriptions. Waffle irons made of cast iron were used less often. A variation of the waffle iron for oven use was the stove-top waffle iron, which was equipped with a mechanism to turn the iron 180 degrees. Waffles were either eaten flat, or rolled up into little sticks.

With so much attention being paid to the color and shape of food in the Middle Ages, it should not surprise us to find that over the centuries cooks came up with an ever increasing number of dishes that pretended to be something else, dishes that are sometimes referred to as “pretend-foods” or “imitation food.”65 One of the possible reasons why such foods evolved may have been the periodic unavailability of foodstuffs. For consumers of the twenty-first century accustomed to buying anything their hearts desire at any time of the year, it may be hard to imagine that for most of human history seasonal cooking was the norm. If a foodstuff was not in season or could not be stored or preserved for future use, the next-best thing diners could do was to make believe they were eating it, by substituting it with something else that was made to look like the real thing. In addition to the “natural” unavailability of food in the Middle Ages, when frozen food did not yet exist, transportation was slow and cumbersome, and trade not nearly as global as it is today, there were the food restrictions imposed by the Christian church for parts of the year. After a long winter with little or no fresh food, the subsequent 40 days of Lent must have left many a believer yearning for a succulent roast. If the cook was able to conjure up a dish that at least visually resembled a roast, even if the taste of the meat substitute was not quite the same, it nevertheless meant that the burden of fasting was alleviated somewhat. Not only was the craving for meat partially met, but since no forbidden foodstuffs were used and no fasting laws broken, the pleasure derived from indulging in imitation meat was a guilt-free one.

Aside from compensating for the lack of a given foodstuff, the imitation food of the period always also displayed a strong sense of playfulness. It is fair to say that in the kitchens of late-medieval Europe the idea of playing with food was elevated to an art form. It was in the creation of a new dish whose composition and presentation contained an element of surprise that the cook could prove the mastery of his craft and demonstrate his artistic talent. As in many other professions of the time, skill, technical know-how, and virtuosity were valued highly in a cook. With an audience that was both well informed and alert, the pressures on the cook to come up with more and more complicated and dazzling creations must have been considerable, especially when the occasion was a festive dinner, or even worse, a festive dinner during Lent.66

Medieval cookbooks, which for the most part reflect wealthy upper-class cooking, are full of imitation dishes for Lent, a time when the consumption of warm-blooded animals, dairy products, and eggs was forbidden to Christians. Sometimes it is just a single sentence at the end of a recipe that contains the fast-day variation of a meat dish. This is the case, for instance, with the medieval favorite known as blanc manger, or white dish, which on fast days was to be prepared with pike meat instead of chicken meat.67 At other times the recipes for imitation dishes are quite elaborate. A fifteenth-century cookbook from northern Germany, written in Low German, provides two detailed recipes for imitation eggs. One uses the shells of chicken eggs to trick the diner into thinking she or he is breaking the fast. The empty shells are to be stuffed with a filling made from ground pike roe (a type of egg acceptable for Lent, one might say), parsley, pepper, saffron, and figs or raisins. The eggs are then put on skewers and grilled.68 The other recipe is the fast-day version of a medieval crowd-pleaser, the giant egg designed to make dinner guests wonder what fabulous animal could have produced such a marvel. Normally an animal bladder filled with a great number of egg yolks was inserted in a larger bladder filled with egg whites, and then cooked. In the case of the giant egg for lean days, the egg yolk consists of ground pike roe mixed with saffron and chopped figs, and the egg white of pike roe and almonds. Once cooked, the giant Lenten egg is cut in two and sprinkled with sugar and ginger.69 In these two examples, fish roe and almonds figure prominently, but fish meat, various other nuts and seeds besides almonds, peas, and bread were also popular ingredients in imitation dishes. Ground almonds, however, were by far the most versatile of ingredients used to prepare a whole range of Lenten foods, from substitutes to cow’s milk, butter, and curds, to cheese, cottage cheese, hedgehogs in different colors, eggs, and egg dishes. Fish meat is shaped into fake roasts, ham, and game birds such as partridges, and fish roe into sausages or bacon. Mincemeat is simulated with chopped almonds and grapes, and cracklings or greaves (the sediment of melted tallow) are made from diced bread.70

As the Middle Ages drew to a close, the church began to allow the consumption of eggs and dairy products on the lesser fast days of the year. This relaxing of the rules is reflected in various recipes for imitation roasts that required eggs and butter as ingredients. To give a meat substitute the appearance of roasted meat, the cook had several options. The most popular was to cover the fake roast with ground gingerbread that had first been fried or roasted. Egg white was sometimes used to simulate the barding (interlarding; inserting of fat in lean meat) of a roast that was otherwise made from fish. French cooks came up with the idea of combining salmon and pike meat for imitation ham and bacon by using salmon to represent the pink meat, and pike the fat.71 At times the diners were fooled by more than just the imitation meat itself. A number of recipes from the period suggest that cooks were also skilled in employing markers to make the illusion even more complete. They would use sauces and broths normally reserved for meat, and not just any meat but the most highly prized of all: venison. There are examples of fake roasts made from fish or crayfish meat, or of sausages made from dolphin meat—which along with barnacle goose and beaver tail was regarded as Lenten food in the Middle Ages—all of them served in a dark and spicy pepper broth that was the hallmark of venison dishes.72

Aside from the obvious desire on the part of the diner to have his meat and eat it, too—in other words, to be a good Christian and still forego the rigors of fasting—what we observe here is a game of make-believe that cooks and dinner guests engaged in. But the Middle Ages did not invent this game, nor were they the last to play it. From ancient Rome several examples of pretend foods have come down to us that were clearly designed to fool the diner. At Trimalchio’s Feast in Petronius’s Satyricon a boar is served that looks ungutted from the outside but when cut open turns out to be filled with delicious sausages. The fact that a number of recipes for this kind of surprise dish can be found in a Roman cookbook from the third century A.D., Apicius’s De re coquinaria (The Art of Cooking), is a strong indication that the boar in the Satyricon was not just the product of a writer’s fertile imagination, but a dish actually prepared by gourmet cooks.73 And if Trimalchio’s wonder dish consisting of a well full of fat fowl, sow’s bellies, a hare sporting Pegasus’s wings, and four figures of flute-playing satyrs pouring a spiced sauce over fishes bears any resemblance to reality, then Roman cooks could easily hold their own against the best royal cooks late-medieval Europe had to offer.74

But important impulses for the evolution of pretend foods may have come from outside Europe as well. Medieval Arab cookery, which subscribed to the heavy processing, coloring, and shaping of food much earlier than European cookery, was full of sophisticated dishes that were designed to look like something else.75 What medieval Europe did was to make such dishes an integral part of lavish banquets. In England these entertaining dishes were known as sotelties, literally “subtleties,” and in France as entremets. The latter word, meaning “between courses,” points to the position such dishes occupied within a multicourse meal. Initially just simple dishes sent to the hall for guests to nibble on as they waited for the next course to arrive, the sotelties or entremets soon became substantially more elaborate and more playful, as cooks began to experiment with unusual colors and color combinations, edible building structures, making cooked food look raw and vice versa, live animals look dead and vice versa, making animals look and act like humans, inventing fabulous creatures, and assembling entire allegorical scenes.76

If the medieval French cookbook known as Le Viandier (The Provisioner) by Taillevent is any indication, then the earliest entremets were nothing more than millet porridge, frumenty or wheat porridge, rice, or such lowly ingredients as the livers, gizzards, and feet of poultry cooked and garnished or served in a sauce.77 All these recipes have one thing in common, however: they contain saffron to give the dishes a golden hue. More sophisticated than these monochrome dishes was the blanc manger that was no longer only a “white” dish, as the name suggests, but was served in two contrasting colors on a plate.78 Jellies, too, soon became the subject of much experimentation by cooks. With jelly squares in different colors the desired checkerboard effect could be achieved.79 And, of course, encasing fish, crayfish, and the like in clear jelly made these animals look as if they were still immersed in water, their natural element.

It has been noted that English cooks, in particular, liked to make towers and castles out of dough.80 Given the strong Italian and Sicilian influence on Anglo-Norman and English cookery, this predilection for edible structures made from dough may have had Italian roots. (See Chapter 3.) Cases in point are the famous Parmesan Pies or Parma Pies that were covered in gold or silver leaf and shaped like towers, complete with crenelations and banners at the top.81 But more than buildings, it was animals that inspired imitation dishes in the Middle Ages. Ground almonds were the basis for hedgehogs that had almond slivers for quills and came in different colors. Alternatively, the meat of fish, fowl, or seafood was often heavily processed and pressed in molds, or stuffed back into the raw skin of the animal.82 Carrying the theme of “the raw versus the cooked” or “nature versus culture” even further was the idea of returning the prepared meat into the full plumage of a decorative bird such as a peacock or a swan, and mounting the animal on a platter in a lifelike pose.83 That even cows or deer were mounted in such a fashion shows that in the Middle Ages there were no limits to what an aristocratic cook and his kitchen staff would be willing to tackle in order to impress a dinner party.84

When cooks no longer saw the need to return the meat of a cooked animal solely to its own skin, this opened the door for a whole new range of culinary tricks. The plumage of a peacock could be stuffed with a goose, that of a dove with some other farce, and the roasted and coated carcass of the dove placed beside it to miraculously make two doves out of one.85 Even entirely new animals were invented by imaginative cooks, such as the Cokagrys, a creature half cock, half piglet, found in the English cookbook known as the Forme of Cury (The [Proper] Method of Cookery).86 And one wonders how medieval diners felt when the sotelties appearing at the table were animals that parodied such human endeavors as going on pilgrimage or riding into battle. The edible pilgrim was either a capon or a pike that was given a roast lamprey as a pilgrim staff, and the knight a cock equipped with paper lance and paper helmet and riding on a piglet.87

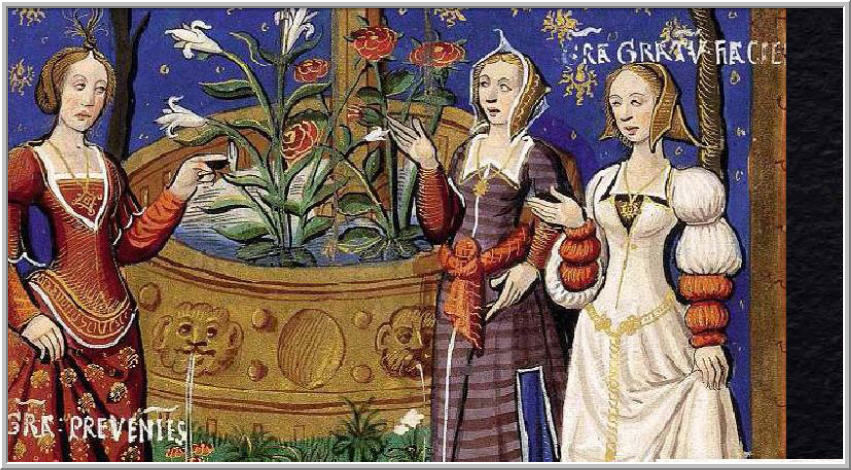

An even more dramatic special effect was achieved when the animal served on a platter was not only mounted and dressed in a lifelike manner, but also made noises, or breathed fire. In a fifteenth-century French recipe collection, the Vivendier (The Provisioner), we find a recipe for making a dead and roasted chicken sing as if it were alive. This is done by filling the tied neck of the bird with quicksilver and ground sulfur, and then reheating the animal.88 More common was the practice of having a boar’s head, swan, piglet, or fish breathe fire by combining cotton with camphor or fire-water, that is alcohol, and lighting it.89 For really grand occasions cooks would assemble a whole range of such edible wonders to form a complete allegorical scene, such as a “Castle of Love,” for instance.90 In the fifteenth century the edible sotelties and entremets were replaced more and more by inedible decorations that no longer required the skill and imagination of cooks but of artists and craftsmen such as painters, carpenters, and metalworkers. They were now the ones producing the tableaux of mythical and religious figures and scenes, among them the “Lady with the Unicorn,” the “Knight of the Swan,” or the “Lamb of God,” Agnus Dei.91

Hand in hand with the development of dishes that made animals appear lifelike, went the development of dishes that made them look dead and cooked while in reality they were still alive. Their inclusion in a meal, like that of the inedible figures made of wood or metal, was purely for the purpose of entertainment. One such creation that

would have animal rights activists up in arms if served today was the live chicken that was made to look roasted. First the bird was to be plucked alive in hot water, then covered with a glaze that gave it the appearance of roast meat, and subsequently it was put to sleep by tucking its head under one wing, and twirling the animal. Then it was to be put on a platter together with other roast meat. What was going to happen next, the cookbook describes as follows, “When it [the chicken] is about to be carved it will wake up and make off down the table upsetting jugs, goblets and whatnot.”92 Another practical joke of this kind was to color live lobsters red by covering them with extra-strong brandy, and mixing them in with the cooked lobsters. An easier way of grossing out especially the women at table, was to serve live cocks and other birds, or live eels in bowls, which when uncovered would have their contents flutter about or slide all over the dining table.93 To this category of dishes also belong the “four-and-twenty blackbirds baked in a pie.” The live birds were to be inserted in a baked pie immediately before serving, and when the top of the pie was cut open, the birds would escape to the amazement of the assembled dinner party. To avoid any of the guests feeling cheated, the Italian cook Maestro Martino suggested filling the pie not just with live birds but with another smaller pie that was edible.94

Sometimes prepared dishes were made to look disgusting just prior to serving. This is the case with two recipes in a Middle English cookbook called the Liber cure cocorum (Book of Cookery). One of them gives instructions for making a meat or fish dish appear raw and bloody by sprinkling the powder of dried hare’s or kid’s blood on it; the other suggests covering meat or fish dishes with “harp-strings made of bowel” to make the food look as if it were full of worms.95 In both cases it is conceivable that the dubious garnish was put on after the dishes had left the kitchen, perhaps by somebody intent on discrediting the cook. This is not as far-fetched as it may seem, since the same cookbook does in fact contain a recipe describing how to get back at a cook. This is to be done by casting soap in his potage, which will make the pot boil over incessantly.96 As this example shows, kitchen humor when carried too far could easily turn into all-out war. In medieval cookbooks recipes for punishing the cook by spoiling or manipulating his food are quite rare. But this is to be expected, given that it was neither in the interest of cooks to give readers any ideas for pranks, nor in the interest of upper-class households to admit to a diners’ revolt. It is in books on magic and, yes, books on warfare, that we find such recipes listed, and the picture they paint of a cook under attack is not a pretty one: He was faced with chickens, pieces of meat, peas or beans made to jump out of the pot with the help of such unsavory additives as quicksilver, vitriol, and saltpeter, or with the pieces of meat in his pot sticking together in one big lump because somebody had poured in comfrey powder.97 It would appear as if the games cooks played with their dinner guests in the form of sotelties and entremets at times came back to haunt them.

NOTES1. Barbara Ketcham Wheaton, Savoring the Past: The French Kitchen and Table from 1300 to 1789 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983), 23.2. For this and the following see Bridget Ann Henisch, Fast and Feast: Food in Medieval Society (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1976), 109.3. The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition, prepared by J.A. Simpson and E.S.C. Weiner, 20 vols. (Oxford, U.K.: Clarendon Press, 1989), “chowder.”4. See chapter 3, esp. the cuisine of southern France.5. Terence Scully, The Art of Cookery in the Middle Ages (Woodbridge, U.K.: Boydell Press, 1995), 236f.; see also Alan S. Weber, “Queu du Roi, Roi des Queux: Taillevent and the Profession of Medieval Cooking,” in Food and Eating in Medieval Europe, eds. Martha Carlin and Joel T. Rosenthal (London: Hambledon Press, 1998), 145–58.6. Henisch, Food and Fast, 67.7. Ibid., 59–65.8. Scully, The Art of Cookery, 40.9. See chapter 6; and also Melitta Weiss Adamson, “Gula, Temperantia, and the Ars Culinaria in Medieval Germany,” in Nu lôn ich iu der gâbe: Festschrift for Francis G. Gentry, ed. Ernst Ralf Hintz (Göppingen, Germany: Kümmerle, 2003), 112f.10.Scully, The Art of Cookery, 243.11.Ibid., 246.12.See ibid., 243–45; Henisch, Fast and Feast, 75–82; and Stefan Weiss, Die Versorgung des päpstlichen Hofes in Avignon mit Lebensmitteln (1316–1378): Studien zur Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte eines mittelalterlichen Hofes (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 2002).13.Wheaton, Savoring the Past, 18.14.Cf. Henisch, Fast and Feast, 97.15.Scully, The Art of Cookery, 86f.16.Henisch, Fast and Feast, 96.17.Scully, The Art of Cookery, 92.18.Henisch, Fast and Feast, 89.19.Scully, The Art of Cookery, 94.20.Wheaton, Savoring the Past, 23.21.Scully, The Art of Cookery, 94.22.Wheaton, Savoring the Past, 24.23.Maggie Black, “Medieval Britain,” in A Taste of History: 10,000 Years of Food in Britain, eds. Peter Brears, Maggie Black, Gill Corbishley, Jane Renfrew, and Jennifer Stead (London: English Heritage in association with British Museum Press, 1993), 110.24.Ibid.25.Henisch, Fast and Feast, 97.26.Ibid., 92.27.Odile Redon, Françoise Sabban, and Silvano Serventi, The Medieval Kitchen: Recipes from France and Italy, trans. Edward Schneider (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 19f.28.Henisch, Fast and Feast, 87.29.Scully, The Art of Cookery, 99f.; see also Redon et al., The Medieval Kitchen, 20.30.Scully, The Art of Cookery, 95.31.Redon et al., The Medieval Kitchen, 21.32.Melitta Weiss Adamson, Daz buoch von guoter spîse (The Book of Good Food): A Study, Edition, and English Translation of the Oldest German Cookbook (Sonderband 9) (Krems, Austria: Medium Aevum Quotidianum, 2000), 30 and 93 (“A stuffed roasted suckling pig”).33.Ibid., 96 (“The following tells about stockfish”).34.Terence Scully, The Vivendier, A Fifteenth-Century French Cookery Manuscript: A Critical Edition with English Translation (Totnes, U.K.: Prospect Books, 1997), 44f. (“To cook a fish in three ways and styles”).35.See Wheaton, Savoring the Past, 23f.; Scully, The Art of Cookery, 98; and Henisch, Fast and Feast, 41f.36.See Scully, The Art of Cookery, 92; Henisch, Fast and Feast, 144; and Adamson, The Book of Good Food, 22 and 93 (“A stuffed roasted suckling pig”).37.Adamson, The Book of Good Food, 22.38.For the following on food adulteration and quality control see P.W. Hammond, Food and Feast in Medieval England (Stroud, U.K.: Alan Sutton, 1993), 80–87.39.See Judith Bennett, Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: A Woman’s Work in a Changing World, 1300–1600 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).40.Henisch, Fast and Feast, 78.41.For a depiction see Hammond, Food and Feast, 85; and Henisch, Fast and Feast, 85.42.Hammond, Food and Feast, 87f.43.Wilhelm Abel, Strukturen und Krisen der spätmittelalterlichen Wirtschaft (Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer, 1980), 31.44.Ibid., 32.45.Hieronymus Bock, Teutsche Speißkammer: Inn welcher du findest / was gesunden vnnd kranncken menschen zur Leibsnarung von desselben gepresten von noeten/Auch wie alle speis vnd dranck Gesunden vnd Krancken jeder zeit zur Kost vnd artznei gereichet werden sollen (Strasbourg: Wendel Rihel, 1550), fol. 54r-v.46.Hammond, Food and Feast, 88f.47.Henisch, Fast and Feast, 81.48.Bock, Teutsche Speißkammer, fol. 107r.49.Hammond, Food and Feast, 89.50.For this and the following on substitute foodstuffs see Hans Wiswe, Kulturgeschichte der Kochkunst: Kochbücher und Rezepte aus zwei Jahrtausenden mit einem lexikalischen Anhang zur Fachsprache von Eva Hepp (Munich: Moos, 1970), 82f.51.Hammond, Food and Feast, 130.52.Redon et al., The Medieval Kitchen, 23f.53.Scully, The Art of Cookery, 112.54.Redon et al., The Medieval Kitchen, 29.55.For this and the following on food coloring see C. Anne Wilson, “Ritual, Form, and Colour in the Medieval Food Tradition,” in ‘The Appetite and the Eye’: Visual Aspects of Food and Its Presentation within Their Historic Context, ed. C. Anne Wilson (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), 17f.56.Redon et al., The Medieval Kitchen, 26.57.Wilson, “Ritual, Form, and Colour,” 19.58.Scully, The Art of Cookery, 114.59.Redon et al., The Medieval Kitchen, 26.60.Scully, The Art of Cookery, 115.61.See Constance B. Hieatt, “Medieval Britain,” in Regional Cuisines of Medieval Europe: A Book of Essays, ed. Melitta Weiss Adamson (New York: Routledge, 2002), 28.62.Wiswe, Kulturgeschichte der Kochkunst, 101.63.Adamson, The Book of Good Food, 96 (“This is a good salmon dish”).64.For the different molds and waffle irons see Wiswe, Kulturgeschichte der Kochkunst, 102.65.Scully, The Art of Cookery, 104; and esp. Melitta Weiss Adamson, “Imitation Food Then and Now,” Petits Propos Culinaires 72 (2003): 83–102.66.Cf. Henisch, Fast and Feast, 101f.67.Adamson, The Book of Good Food, 92 (“If you want to make blanc manger”).68.Hans Wiswe, “Ein mittelniederdeutsches Kochbuch des 15. Jahrhunderts,” Braunschweigisches Jahrbuch 37 (1956): 39 (“If you want to make eggs in Lent”).69.Ibid., 39 (“If you want to make a big egg in Lent”).70.See esp. Adamson, “Imitation Food,” 91.71.Wheaton, Savoring the Past, 12.72.Adamson, “Imitation Food,” 91.73.Melitta Weiss Adamson, “The Greco-Roman World,” in Regional Cuisines of Medieval Europe: A Book of Essays, ed. Melitta Weiss Adamson (New York: Routledge, 2002), 6.74.See Satyricon, in Petronius, with an English translation by Michael Heseltine; Seneca Apocolocyntosis, with an English translation by W.H.D. Rouse (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1939), 55.75.Wilson, “Ritual, Form, and Colour,” 18.76.For the evolution of the sotelty or entremets see esp. Scully, The Art of Cookery, 104–10.77.Terence Scully, ed., The Viandier of Taillevent: An Edition of All Extant Manuscripts (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1988), 286 (“Faulxgrenon,” “Pettitoes: feet, livers and gizzards,” “Frumenty,” “Taillis,” and “Millet”) and 288 (“Fancy rice for meat-days”).78.Ibid., 301 (“A particoloured white dish”).79.Terence Scully, ed., The Neapolitan Recipe Collection: Cuoco Napoletano (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000), 191 (“Jelly like a checkerboard”).80.Scully, The Art of Cookery, 106.81.Scully, Viandier, 300f. (“Parmesan pies”). Crenelations are a “notched battlement made up of alternate crenels (openings), and merlons (square saw teeth)”; see Joseph and Francis Gies, Life in a Medieval Castle (New York: Harper & Row, 1979), 225.82.Scully, Viandier, 286f. (“Stuffed poultry”).83.Ibid., 304 (“Peacocks [redressed in their skin]”).84.Scully, The Art of Cookery, 106.85.Ibid., 107.86.Constance B. Hieatt and Sharon Butler, eds., Curye on Inglysch: English Culinary Manuscripts of the Fourteenth Century ( Including the Forme of Cury) (Early English Text Society SS.8) (London: Oxford University Press, 1985), 139 (“Cokagrys”).87.Scully, The Art of Cookery, 107; for a depiction of this peculiar knight, see the book cover of Jean-Louis Flandrin and Carole Lambert, Fêtes gourmandes au Moyen Âge (Paris: Imprimerie nationale Éditions, 1998).88.Scully, Vivendier, 82f. (“To make that chicken sing when it is dead and roasted”).89.Ibid., 44f.90.See Scully, The Art of Cookery, 108.91.Ibid., 108f.92.Scully, Vivendier, 81 (“To make a chicken be served roasted”).93.For the above examples see Wiswe, Kulturgeschichte der Kochkunst,97.94. Redon et al., The Medieval Kitchen, 32.95.Melitta Weiss Adamson, “The Games Cooks Play: Nonsense Recipes and Practical Jokes in Medieval Literature,” in Food in the Middle Ages: A Book of Essays, ed. Melitta Weiss Adamson (New York: Garland, 1995), 178 and 183.96.Ibid., 184.97.Ibid., 185–88.

By Melitta Weiss Adamson in "Food in Medieval Times", Greenwood Press, USA-UK, 2004, excerpts p.55-81. Adapted and illustrated to be posted by Leopoldo Costa.

.jpg)